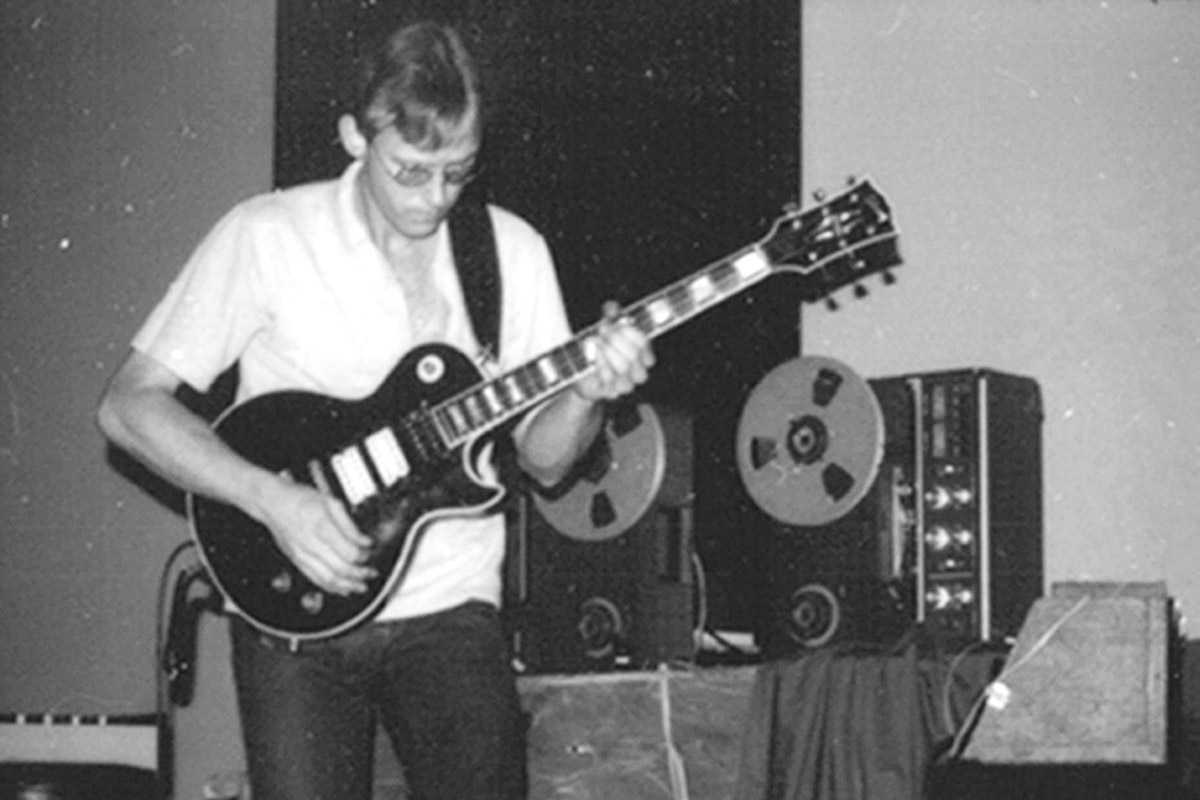

Barry Cleveland | Meet The Team

Barry Cleveland’s music spans a spectrum from avant-rock and world fusion to ambient and free improvisation. His fascination with spacey sounds was already apparent when he gave his first public performance in junior high school with the reverb control on his amp turned all the way up, and close encounters with a fuzz box and an Echoplex forever altered his life’s trajectory. Early in his writing career, Cleveland penned Joe Meek’s Bold Techniques, which details the work of the legendary British recording iconoclast, and later went on the serve as an editor at Guitar Player magazine for 12 years. Current activities include conducting interviews for his blog The Lodge, composing music for picture, and contributing to Stompbox: A Visual Exploration of the Guitar Pedal.

You are both a musician and a writer. Did those careers unfold simultaneously or independently?

I started playing guitar seriously when I was about 12. My older brother was into music and introduced me to a lot of great stuff that I probably wouldn’t have heard otherwise; and my parents had some Les Paul records that really captured my imagination. I played heavy rock early on, but by the time I was in high school I had gotten deeply into psychedelic and progressive rock and was also doing a lot of improvised space music with a like-minded guitarist. After leaving college I toured the southeast with a mixed-race funk and soul band for a year.

In 1986, I got my first record deal when Larry Fast signed me to his Audion Recording Company label and released my Mythos album. Larry was the keyboardist in Peter Gabriel’s band and also made a lot of fantastic synthesizer records under the name “Synergy.” I made several other records over the years, the most recent one being my collaboration with French guitarist and synthesist Richard Pinhas that was released on the Cuneiform label. The music on Mu began as pure improvisation, and I dubbed in additional guitar and other instruments and did lots of post-production afterward. The rhythm section was Michael Manring on bass and Brazilian drummer Celso Alberti, both of whom also played on my Hologramatron album.

I got into writing by accident. A friend of mine asked if I wanted to come in and do some things to help out with Mix magazine, which at the time was the trade magazine for the studio business. I wound up becoming the editor of the Mix Master Directory and The Recording Industry Sourcebook, and eventually Mix editor George Petersen asked if I’d like to try my hand at writing gear reviews. The Empirical Labs Distressor was my first review. That unit had just come out and I predicted it would become an instant classic, which it did, so that was an auspicious beginning. I worked with Electronic Musician, too and eventually got hired at Guitar Player where I was an editor for 12 years. Early on I wrote a book on Joe Meek and perhaps in part because of that book he’s become recognized as one of the most innovative and important figures in the history of recording, whereas before he was merely an obscure footnote in British recording history. At Guitar Player, I interviewed hundreds of guitar players and reviewed thousands of products including hundreds of effects pedals.

Tell us about your collaboration album with Richard Pinhas.

The core tracks on Mu—including the 26-minute “I Wish I Could Talk In Technicolor”—were completely improvised in a single afternoon. Richard, Michael Manring, Celso Alberti, and I just began playing and recorded the results. There was no discussion of key, tempo, style, or any of the other usual considerations. We were extremely fortunate to get as much good material as we did in such a short time, as that was our only opportunity to record together while Richard was in the U.S. After that, I recorded additional guitars and other instruments, Celso replaced his electronic drum tracks with acoustic drums and did some percussion overdubs, and I spent an inordinate amount of time mixing it.

The music on Mu is largely based on live looping, which is Richard’s forte. All of his sounds were produced using an Eventide H3000 and a Zoom Driver 5000 distortion pedal. Most of my sounds came from a Fractal Audio Axe-Fx II Ultra and too many pedals to list. Even Michael Manring looped his bass, most notably on the opening of “Zen/Unzen.”

On a lighter note, earlier in the interview Jeff and I were sitting on the couch together and he was playing rough mixes of tracks that would eventually appear on his Jeff album. When the solos would come on, he’d glance over at me, raise his eyebrows, and play air guitar, as if he were seeking my approval. At that moment I thought to myself, “If I were to die tomorrow, my life would have been complete.”

Are you playing sitar on one track?

Not exactly, Electro-Harmonix has a pedal called the Ravish Sitar that does a pretty good job of making a guitar sound like a sitar. There’s a very atmospheric section on “I Wish I Could Talk In Technicolor” that has a slightly Indian feel to it, so I used the Ravish to lay down a pseudo-tambura drone section, which was fairly convincing. Then, I decided to try creating a melodic part and although I was just going to fool around with it I engaged record so I’d be able to listen to what I’d done as I was getting ideas together. Once I started, however, I found myself playing a somewhat bizarre interpolation of the melody from The Beatles’ “Within You Without You,” sustaining some notes for long stretches and otherwise drastically altering the phrasing. I felt as if I was in some sort of trance, playing entirely in the moment without conscious consideration. Then, when I listened back, I nearly fell out of my chair laughing. My part synchronized with Michael’s bass lines perfectly, creating these beautiful harmonic shirts that sounded as if they were intentionally composed. That’s a perfect example of the magic of improvisation. I live for that kind of stuff.

I’m assuming you can’t recreate the same improvised pieces live. How does the live performance vary or translate from the recording?

We haven’t played live together, but I was a member of the all-improvisational quintet Cloud Chamber in the ’90s, which recorded an album called Dark Matter and also performed live. Michael Manring was also a member of that group, along with Michael Masley, a multi-instrumentalist best known for playing the bowhammer cymbalom, cellist Dan Reiter, who was in the Oakland Symphony but also studied Indian music with Ali Akbar Khan, and percussionist and hammer-dulcimer player Joe Venegoni. What we found was that even though we went out with no preconceptions or intentions of reproducing the music on the album live, we would often revisit some of those same ideas spontaneously. It was as if the music was just lurking in our collective subconscious and would appear on its own whenever it felt like it, though usually taking a somewhat different form and direction.

This is a subject that really fascinates me. I recently re-launched a blog on my website called The Lodge, which began as a place for long-form artist interviews, but going forward will be about creativity and creative processes. The first interview is with renowned record producer and musician Michael Beinhorn, who wrote an excellent book called Unlocking Creativity, A Producer’s Guide to Making Music and Art.

Who are some of the people that inspired you and your music?

As a kid it was the usual suspects, like Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton, Ritchie Blackmore, Tony Iommi, David Gilmour, and Jimi Hendrix. And I’ve always been in awe of Jeff Beck, the greatest rock guitarist of all time. Two other guitarists that were important influences were Randy California of Spirit and Erik Brann of Iron Butterfly, both of whom were quite inventive and used effects brilliantly. The progressive rock guitarists that influenced me the most included Robert Fripp, Steve Hackett, Fred Frith, Adrian Belew, and Steve Howe. I recently interviewed Hackett and Howe for the pedal book. On the jazz side there are far too many to list, but the ECM Records guitarists who really blew my mind were Terje Rypdal, John Abercrombie, Bill Frisell, Ralph Towner, and David Torn. More generally, John McLaughlin, Allan Holdsworth, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Joe Zawinul, Paul Motian, and Charles Mingus. While working at Guitar Player I received about 100 CDs a month and was exposed to a huge amount of music of all styles. For example, that’s how I gained a greater appreciation of Manuel Galbán, Ali Farka Touré, Nels Cline, Eivind Aarset, Mike Keneally, John Frusciante, and Ben Monder. I could name hundreds more.

Of all the interviews you’ve done, which ones made the greatest impression on you?

That’s a difficult one to answer, as there have been so many. My first interview for Guitar Player was with Mark Knopfler and it began very badly because he was in a cranky mood, but ended up being really good once he realized I’d done my homework and wasn’t just going to ask him the same old questions. Shortly after that I interviewed Ry Cooder for a cover story and when I arrived at his studio at the Santa Monica Airport I found him half asleep in the front seat of a very cool old car from the 1950s. My tape recorder failed and we cruised into town in that car to get another one, which was tremendous fun. My interview with Eric Clapton in New York was also memorable. He’d released his Robert Johnson cover album and his press said he’d “returned to the blues,” so I asked where he’d been in the meantime? He said Johnson represented the “pure blues” and I pointed out that although he played nothing but blues on the few recordings we have of him, he also played all kinds of other music, and suggested that Clapton was romanticizing him just as his fans had done—“Clapton is God”—in the ’60s. From that point on the conversation got really interesting. One of the things I’m very thankful for is that many of the artists I met through the magazine became friends.

Two of those artists are John McLaughlin and Allan Holdsworth. How did you meet them?

Our paths first crossed when I facilitated a joint interview with the two of them that appeared in the October 2005 issue of Guitar Player magazine. I thought it would be both fun and enlightening to get two of my favorite guitarists together and let them interact with one other, which it was, though they spent much of the time expressing mutual admiration and reminiscing about playing with Tony Williams. Then, over the years, I got to know them individually as a result of conducting additional interviews and meeting up on occasion. The last time I spoke with Allan was about scheduling an interview for the pedal book (Eilon had already photographed his Yamaha delay pedal) just a few days before his passing. He sounded happy and upbeat.

You said that Jeff Beck is the greatest rock guitarist of all time. Did you ever interview him?

Yes. He was in Los Angeles for the L.A. Auto Show and I flew down from San Francisco to meet him at a photo studio. One of the things that stood out when I was prepping for the interview was how he had started to achieve mainstream success several times throughout his career and each time had done something to derail it. I asked him if he feared success and he became very thoughtful, leaned back on the couch with his feet stretched out, and began talking about his mother and how she had taught him not to take himself too seriously—as if he was in a psychiatrist’s office. But he also pointed out that after reaching stardom Clapton had become strung out on heroin and Hendrix had overdosed, so maybe it was as much about self-preservation as fear. I’m pretty sure he’d never gone that deep about himself personally in previous interviews.

On a lighter note, earlier in the interview Jeff and I were sitting on the couch together and he was playing rough mixes of tracks that would eventually appear on his Jeff album. When the solos would come on, he’d glance over at me, raise his eyebrows, and play air guitar, as if he were seeking my approval. At that moment I thought to myself, “If I were to die tomorrow, my life would have been complete.”

Cover photo: Jeff Fasano

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

[…] auspicious beginnings and continued growth, veteran progressive guitar wizard and journalist Barry Cleveland, who discusses his life on both sides of the glass, behind a pedal board and in front of a […]