Klon Centaur #005 | Stompbox Stories

When guitarist Suke Cerulo took a leap of faith on an exceedingly expensive, unknown overdrive pedal nearly two and a half decades ago, there was no way he would’ve known the part he was about to play in stompbox history.

As a player, Cerulo knows his stuff. Currently the Lead Guitar Program Director at the New York City Guitar School, he’s toured and recorded with acclaimed six-strings-centric bands like Schleigho (of which he was a co-founder, along with fellow Berklee School of Music classmates), Lynch, and Conehead Buddha, sharing stages along the way with legends spanning the Allman Brothers and Derek Trucks to Maceo Parker, G. Love, and John Scofield. But on that fateful day long ago, Cerulo didn’t know what the roughly handmade pedal was that he stumbled onto and couldn’t really afford, other than it sounded better than any other he’d ever heard. Nor did he expect it would become a collector’s item whose value would exceed his guitar (and never leave his board, even to this day).

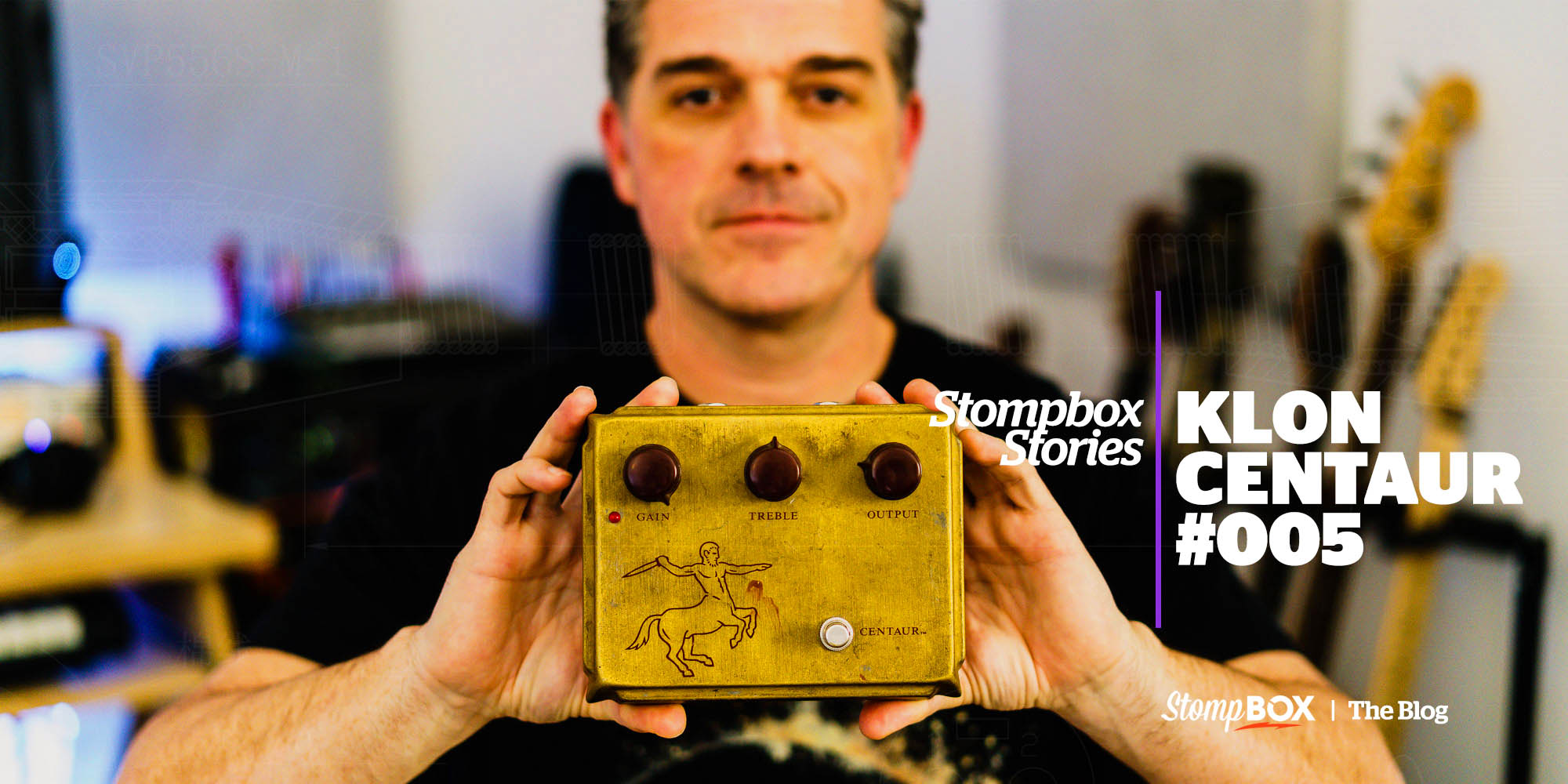

By chance, Cerulo had acquired the very first unit sold to the public of the Klon Centaur, perhaps the most storied pedal to come out of the last thirty years. Today, revered players from James Hetfield to Jeff Beck to Joe Bonamassa all use the Klon for its crystal clear, yet hefty, tone like none other. Way back when, though, Cerulo indeed proved to be the sole guitar cowboy to saddle up the “Golden Horsie.” Here, he relays to Stompbox his exclusive first-person account of this revolutionary discovery that changed not just Cerulo’s tone in its wake, but stompbox culture forevermore as we know it.

Sometime back in early 1995, I happened across a guitar pedal that would change the way the world thought about pedals. Enough to create a subculture of clones – Klones – more than any other pedal. Enough to be considered the Holy Grail of overdrive pedals. Enough to make me feel incredibly lucky!

While attending Berklee College of Music in Boston, I’d gotten to know the owner of Bay State Vintage Guitars , Craig Jones. He used to have a small shop near Back Bay, and I bought my 1971 Fender Twin there. I was constantly at Bay State having Craig mod my amp, playing his amazing collection of vintage gear, and learning all about tube amps from his wisdom. One particular day, an unassuming man sporting a messenger bag walked in, and said that he had a pedal that he wanted to put on consignment.

I was in the back of the shop, but could still hear Craig and this guy talking. To demonstrate the pedal, the guy explained he wanted to use a Gibson SG and plug into the Fender Twin that was on display in the shop (very similar to mine, in fact). Craig said it was okay, so he pulled this big, ugly pedal out of his bag and plugged it in. It only took him three notes before I whirled around and went right up to him to ask him what it was.

What I heard come out of that Fender Twin in that moment was the sweetest, most singing overdrive tone I’d ever heard. I immediately knew I had to get that pedal – and above all, that tone. To me, this magical invention seemed like the exact opposite of my Tube Screamer. The tone was huge, and yet somehow clear, even though it was overdriven. It sounded so open, like it was almost anti-compressed.

Curiosity piqued, I asked the pedal-bearing stranger, “So, is that a vintage pedal?” “No, I built it,” he said. We started talking, and I found out his name was Bill Finnegan. A graduate of MIT, he and his buddy had spent four years developing this overdrive pedal he called the “Klon Centaur.” It was certainly a distinctive name, all right!

Not too long into our conversation, the owner of the store interjected, asking how much he wanted to sell the pedal for. Bill replied that he was thinking of something in the $250 range. Craig said that was too much, and that no one would pay that amount of money for an overdrive. I understood that: ye olde Ibanez Tube Screamers were going for well under $100 at the time. Regardless, I couldn’t let that pedal, this majestic Klon Centaur, walk out the door without me.

Sensing my interest, Bill actually offered to come over to my house and demo the pedal with my own guitar and amp. That was so cool of him – I couldn’t believe this guy was offering to go the extra mile like this. I was playing then with the band Schleigho, and we were on the road a lot, so finding a time was tough; eventually, however, we arranged a day for him to give me an insider tour of the Klon’s magic.

When Bill showed up at my rehearsal space one afternoon soon after, he proceeded to go into the utmost detail of his creation. In all, he spent over three hours with me, taking me through the Klon’s ins and outs. He explained that when he built and tested the pedal, he’d used a Gold Top Les Paul, so the pedal especially shines with humbucker pickups.

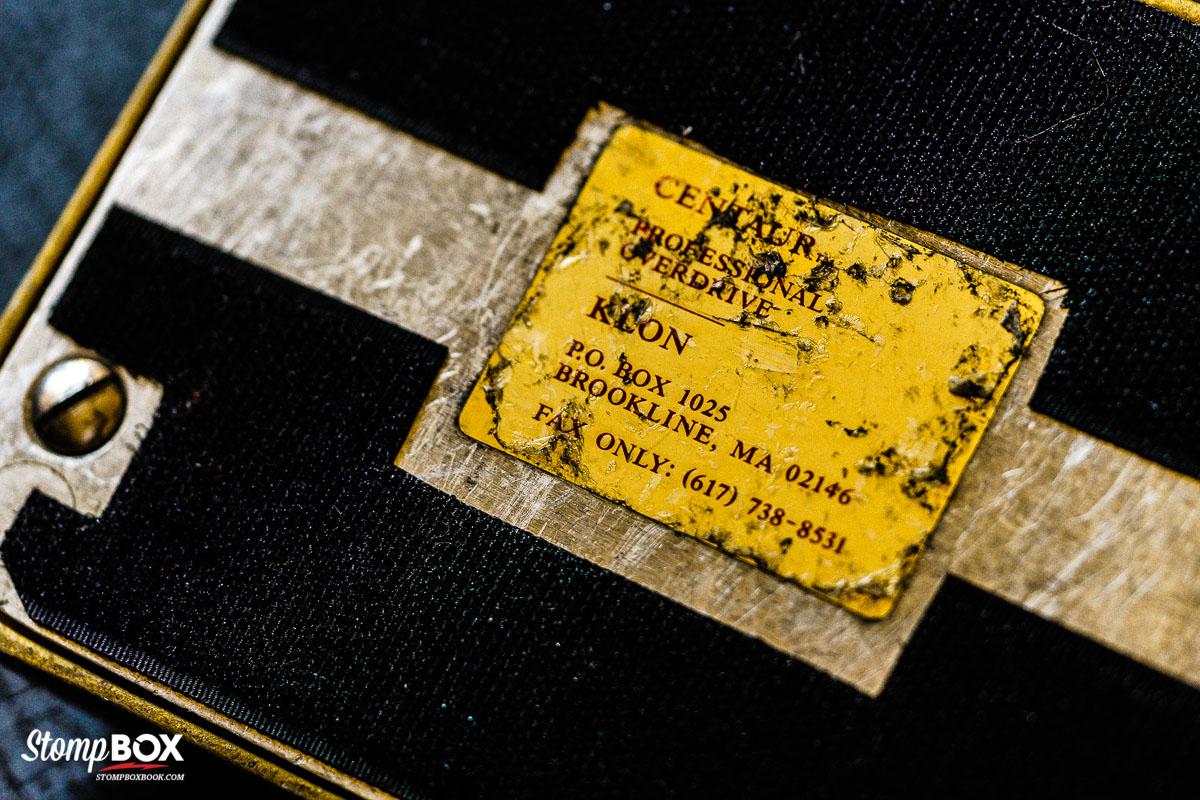

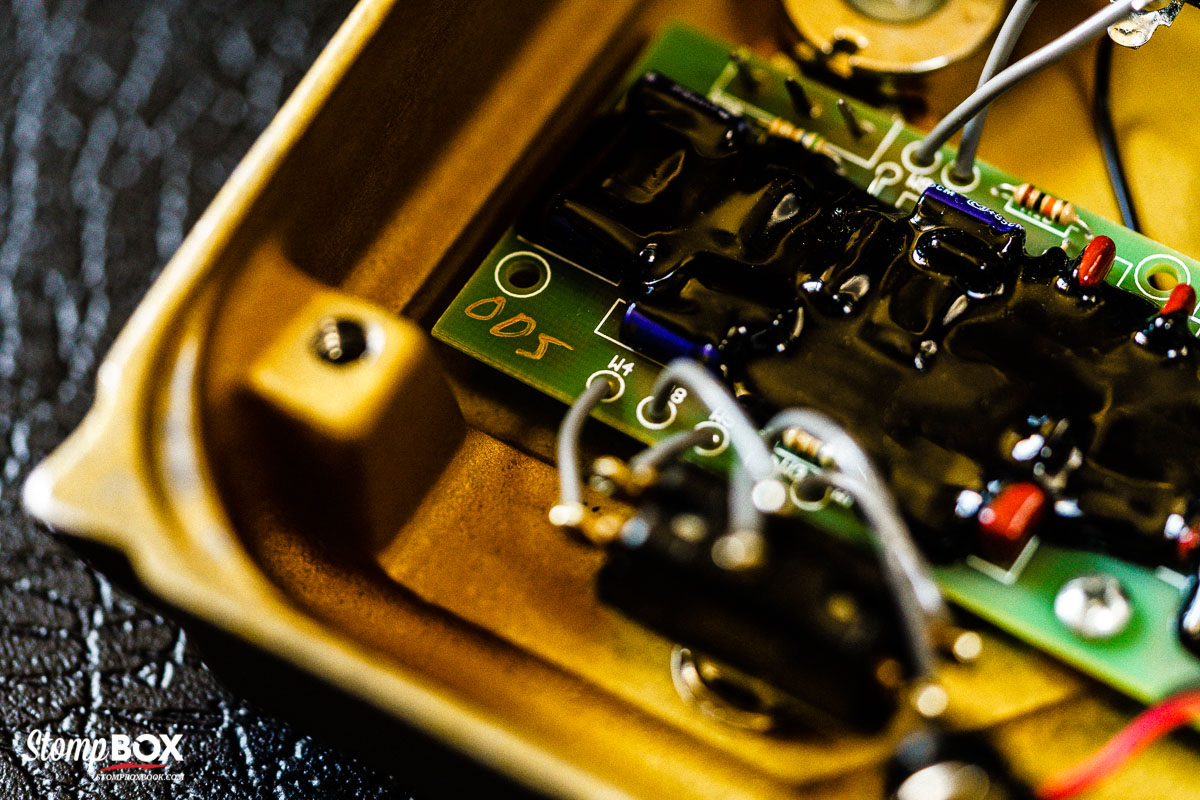

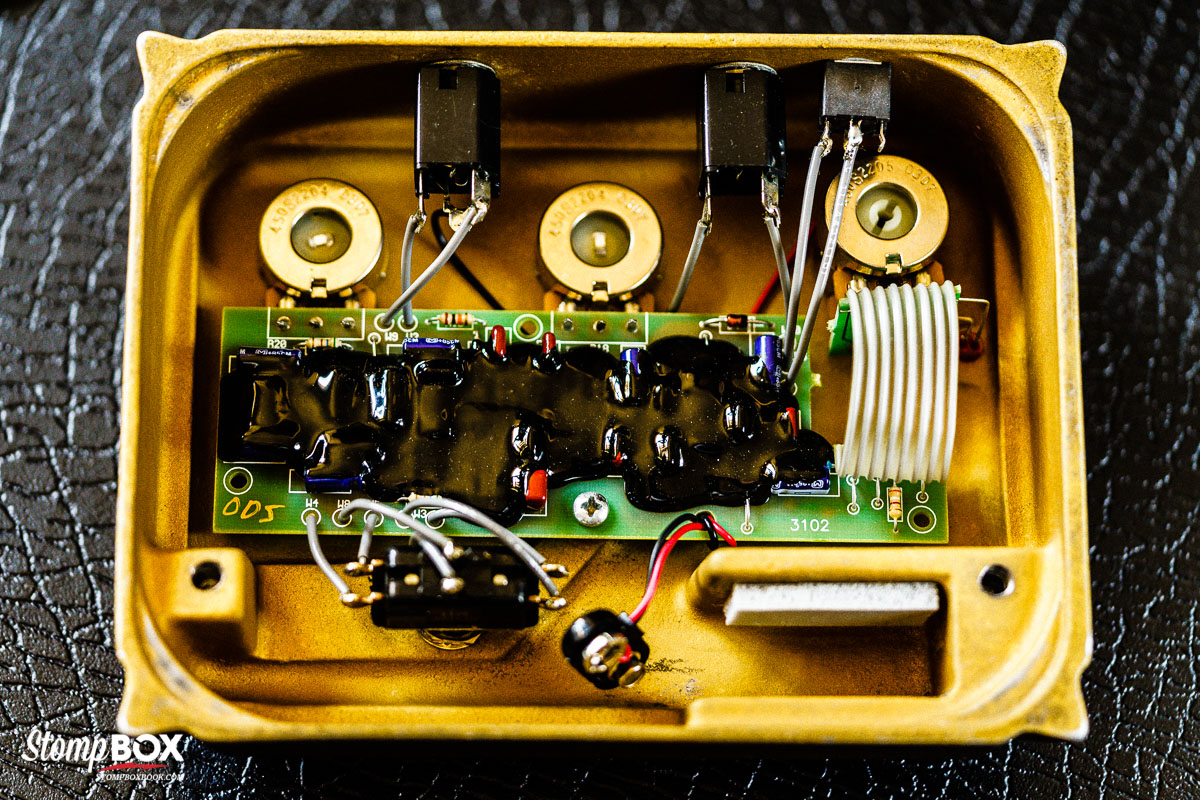

Inspecting the pedal, I asked Bill why the product sticker on the bottom said “fax only” when it came to contact info. He said his girlfriend didn’t want all kinds of phone calls coming to the house; I thought that was a little ridiculous – but in hindsight, she may have been on to something! Bill mentioned that he felt the pedal works best with a battery, but he’d still put a 9v adapter jack on there (for which I had to buy a special jack from Switchcraft and splice it onto an old BOSS adapter). He even opened up the pedal’s enclosure to show me the Klon’s main board, the guts of which Bill had drizzled with paraffin wax. He told me he’d done that to protect it from the elements. I believe also he did it to protect his work from being copied – although once word got out about Finnegan’s creation, it didn’t take long until someone melted off the wax, revealed the components, and started the “Klone” wars.

After the first year using the Klon, I saw Bill to catch up and replenish my stash of his business cards. I asked him how the Klon’s sales were going, and he said he’d already sold a few hundred pedals! I was surprised: that seemed like a lot for a one-man operation like Bill’s. In fact, he told me he was hand-making every pedal in his apartment, and each one took a long time. After that, I started to see Bill’s pedal enter mainstream consciousness.

In his demo, Bill really emphasized how versatile the Klon’s tone control was. He said he’d thought of it primarily as a boost. “This pedal really is different,” he explained, “because it’s meant to enhance your already existing guitar tone, not color it.” But when I asked what the Klon sounds like when the drive knob is all the way up, he said without pausing, “A cranked Marshall.” Cranking it up, it sounded indeed like just that – or maybe better. I was sold – this pedal was ridiculous.

When I told Bill I wanted to buy the pedal, I also asked how many overall he’d made. He said I was actually his first real Klon customer, and that he had only made eight of them so far! Needless to say, I was hesitant hearing this. The Klon Centaur was a brand new thing to me and the guitar community, and it cost a ton of money (for a poor guitar player like me, anyway, just barely out of Berklee). I asked if I could have serial #001, but he said the first few Klons he’d made were kept for his family; I could have serial #005, however.

Really, I had no choice at that point – resistance was futile. That day, I bought Klon #005 and never looked back. As I got to using it, I discovered the pedal had just so much headroom. I could blast it onstage through my Gibson ES-175 and my 1971 Fender Twin, and it would cut through any volume level and mix with clarity and a full, bold tone.

From 1995 until almost 2005, I toured the U.S.A. playing almost 200 dates per year. The Klon Centaur was the only pedal I used, and I ran it off batteries as Bill instructed. I continually had people asking me about my tone, and the pedal in particular. Bill had given me a bunch of his business cards: I ended up giving them all away, as each night I got the question, “Whoa, what is that pedal?”

After the first year using the Klon, I saw Bill to catch up and replenish my stash of his business cards. I asked him how the Klon’s sales were going, and he said he’d already sold a few hundred pedals! I was surprised: that seemed like a lot for a one-man operation like Bill’s. In fact, he told me he was hand-making every pedal in his apartment, and each one took a long time. After that, I started to see Bill’s pedal enter mainstream consciousness. While watching the Metallica documentary Some Kind of Monster, I spotted a Klon on Kirk Hammett’s board. Seeing my old friend, I jumped out of my seat. Now even Metallica knew the lure of the Centaur. Really, Klon mania had only just begun…

A few years later at a gig, a sound guy dropped the heavy round plate off the bottom of a mic stand onto my Klon, crushing the tone pot. I contacted Bill Finnegan, and he told me the next time I was back in town to him meet at a local music store in Porter Square near Boston. When I arrived, Bill was there talking to the guys in the shop. Seeing me, he motioned towards the back of the store. On the counter, he opened up my Klon, removed the squashed tone pot: he then bent it back into shape with his teeth, soldered and reinstalled it. I breathed a sigh of relief: the Klon was back in business.

Speaking of business, I couldn’t believe Bill’s relentless pursuit of getting it done. Once again, I casually asked him how sales were going; when he mentioned that he was now up to three thousand Klons sold, I almost fell over. Bill added that the pedal’s popularity was actually growing beyond his ability to make them – now that folks like Warren Haynes, Joe Perry and John Mayer had started using the Centaur.

Years later, I was playing a show in Jamestown, New York. In-between sets, I noticed four guys hovering over my pedal board. I went over, and one of the guys looked up and said, “Dude! You’ve got an original ‘Gold Horsie’ Klon!” [Editor’s Note: “Gold Horsie” refers to the original Klon’s enclosure, whose gilt surface was emblazoned with a distinctive line drawing of its rearing half-man, half-horse namesake.]

I quickly told him my story, and he said, “Man, these things are selling for a few thousand dollars on eBay.” I was shocked, yet again, but hardly surprised. I knew that Bill had recently declared that he was done making any new Klons, and would just complete the backorders. Sure enough, when I checked on eBay, the cheapest original Klon Centaur was $2,000, going up to $3500 for a “low-serial-number” model. Of course, what was considered a low serial number? Well, this guy was selling Klon #300! Ha!

Seeing that, I realized the magnitude of this epic, now iconic pedal coming into my life. I now felt like one of the luckiest guitar-playing, gear-loving souls ever. I was so grateful to have had the random chance to bump into the Holy Grail of overdrive pedals and its creator that day in ’95 and get one of the first five Klon Centaurs that Bill ever made. I have since taken it off my pedal board, and it now never leaves my home, but my Klon is still never far from my heart…

– Michael Suke Cerulo

3 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

Great article!

[…] more, our Stompbox blog this month features an incredible story by Matt Diehl on only the fifth Klon Centaur to ever roll off the workbench of the brilliant Bill Finnegan, and the first ever made available […]

Very good writing, Matt. And a great story. I didn’t know Finnegan was an MIT grad! No wonder his design is so cool. It sounds good for a reason. Finnegan knew how to do something called “pole-zero compensation” that was actually required with the op-amps available back in the 90’s. He was definitely a real engineer!